注目

- リンクを取得

- ×

- メール

- 他のアプリ

Theories of credit money in Japanese Marxian economics: 2 Okahashi in Banknote controversy

A.

Okahashi in Banknote controversy

“Banknote

controversy” on inconvertible banknote arose in Japan from the mid-1950s to the

early 1960s. The gold standard suspension in the Great Depression of the 1930s.

Then, after World War II, the advanced capitalist economies recovered and

restored the exchangeability between main currencies. However, the

convertibility to gold remained unrecovered. Can the currency circulate

normally without convertibility? The controversy began with the proposition by

Tamotsu Okahashi that “even inconvertible banknote is also credit money, not

state paper money.” State paper money is fiat money, which has no value in

itself and can circulate only by state force. Although money is not necessarily

tangible such as banknotes, Okahashi and his contemporaries mainly treated the

banknote as money with finality. Therefore, the banknote in this controversy

means the money itself.

Many in the

Banknote controversy disagreed with Okahashi’s theory, arguing that inconvertible

money is state paper money that can circulate only by state compulsion.

Okahashi’s argument did not spread. Therefore, it is essential to quote some

paragraphs of Okahashi’s book.

A.1 Creation of

credit money

According to

Okahashi, credit money arises from bill transactions. In the commodity economy,

obtaining a commodity needs paying money. However, the delivering money need

not occur at the same time as receiving the commodity. It is also possible to

receive the commodity first and pay the money after a certain period of time.

The promise to “pay later” is the bill of exchange, which is the basis of

credit money. If the bills cancel each other out, the proper money is no longer

needed. Thus, “they act absolutely as money.” (Marx [1981] p.525)

Okahashi

explains the creation of credit money is as follows:

In the monetary

economy, receiving something must correspond to giving another. There can be no

receiving without giving anything. Therefore, only if a person contributes to

society can he receive what deserves his contribution. his mutual reward

relationship is always strictly secured in the monetary economy. Thus the

commodity circulation consists of giving and receiving through money. However,

this mutual reward relationship does not necessarily coincide. … In a particular stage of development of the circulation, the producer

can receive something without giving anything. In the production relationship that

allows him to delay giving for a certain period of time, a credit relationship

enables receiving before giving. There, money becomes the means of payment.

The credit

relationship gradually develops with money as the means of payment and gives

the bill a monetary function. The bills become so-called commercial money.

Commercial money arises from the mutuality of giving and receiving credit

between producers and merchants. Such complicated mutual credit relationships exist

in the roots of the bill circulation. Therefore, the bills can circulate as

means of payment or purchase instead of the proper money. As long as the

receivables and debts cancel each other out, no proper money is needed. In this

way, bills can function instead of money because the mutual credit between

producers and merchants establishes a corresponding reward relationship between

giving and receiving. Thus, in general, commercial bills are the first

alternative to the money function as a means of payment. (Okahashi [1957] pp. 109-110)

The credit money

is, in essence, a bank bill or bank deposit issued by bill discounting and

circulates in place of a private bill. It is the money as a payment instrument

peculiar to the banking system, based on the circulation of bills, and has

developed from commercial money. Just as the money arises from commodity

circulation, commercial money arises from developed commodity circulation with

credit relationships. When banks emerge, the credit money arises through the lending

of credit by banks. (ibid., p. 137)

Okahashi

explains that credit money circulates instead of a commercial bill. Then, The

commercial bill is used instead of the proper money. The proper money is a kind

of commodity and is selected among all the commodities. As long as the credit

money is issued on the basis of bill circulation, it is neutral to the economic

process. (This neutrality will be described later in section A.4.)

Thus, the matter

is not whether convertible or inconvertible, but how the banknotes are issued. When

they are issued not based on bill circulation, they are non-proper banknotes.

Because inconvertible

banknotes issued by bill discounts and securities-backed loans can contract

depending on the situation of circulation, they would not remain in circulation

forever. In contrast, when inconvertible banknotes are thrown into circulation

with unproductive public bonds as collateral, they cannot contract and remains

in circulation as a legal means of payment forever. Indeed, such inconvertible

banknotes remaining in circulation obey the laws of state paper money. Nevertheless,

the inconvertible banknote not originally based on the circulation of paper

money cannot be the same as state paper money. Since the proper banknote is “not

based on monetary circulation, that of metallic or government paper money, but

rather on the circulation of bills of exchange” (Marx [1981] p. 525), it is a

means of circulation peculiar to “commercial circulation” (ibid., p. 529), not

one for general circulation.

Nevertheless,

banknotes have entered the general circulation as legal tender in place of state

paper money because some of them come to be issued on the basis of the money

circulation. Thus, the problem is not whether convertible or inconvertible, but

rather whether the banknote circulates as bill circulation or money circulation

(Okahashi [1957] p.208).

Clearly,

Okahashi shows that the nature of banknotes depends on the financial asset

which the bank receives at their issuing.

A.2 Multiple

ways to issue banknotes and three laws of circulation

Okahashi

explains the multiple ways to issue banknotes and three laws of circulation:

Although the

banknotes are not prescribed as the Bank of Japan’s bills, they are related to

different circulations through the different properties guaranteed. Therefore,

depending on different properties, banknotes flow into circulation according to

different laws and are constrained by these laws. Under the gold standard, just

because the banknotes are obligated to convert to gold does not mean all the

convertible banknotes conform to the same law. Similarly, after suspension of

the gold standard, just because the banknotes become inconvertible does not

mean all the “inconvertible” banknotes are inconvertible paper money, that is,

state paper money. Moreover, conversely, all the inconvertible banknotes do not

have the same effect on circulation. They differ in the circulation law by the

way to enter circulation or the guaranteed properties. Whether the banknote is

legally convertible or inconvertible, the banknote is always tied to and

constrained by gold. Therefore, in this sense, there is no monetary system

other than the gold standard. It does not matter whether the conversion of banknote

to gold is legally obligated or suspended (ibid., pp.214-215).

It is

challenging to understand Okahashi’s claim that the gold standard exists even

without conversion. However, it can be understandable by considering that the

banknotes can circulate on the basis of the bill circulation without gold

conversion. Thus, despite the suspension of the conversion, the gold standard

system could continue.

The following

figure shows the explanation of Okahashi about three laws of circulation.

Table A-1

|

Laws of circulation |

In Marx’s “The Capital” |

Guaranteed property・Backing assets, By Okahashi |

arise from… |

|

Laws of the circulation of bills of

exchange |

v.3, p.525 |

commercial bills、bank accepted

bills |

means of payment |

|

laws of metallic circulation |

v.2, p.192,400 |

securities, gold, non-commercial

bills |

means of circulation |

|

Laws of circulation of paper money |

v.1, p.224 |

state bond, unsecured loan to the state |

metal circulation |

The money based on the bill circulation increases

or decreases, depending on the demand of the commerce. The money based on the metal

circulation arises in exchange for things possessing value, such as gold and

securities, which possess value within or without circulation. The money based

on the paper money circulation is valued as long as it remains within circulation

instead of the metallic money. If its quantity increase more, its value

declines

Okahashi explains

the three ways as follows:

Firstly, banknotes

guaranteed by commercial bills, bank accepted bills, and other bills rest on

the re-discount of commercial bills and are the proper banknotes that follow

the law of bill circulation. However, when the bills securing banknotes are not

directly based on commercial trade, the banknotes obey the law of metal

circulation. When the bills securing banknotes are insolvent and taken over by

the government, the banknotes obey the laws of paper money.

Secondly, banknotes

guaranteed by government bonds do not stand on the general circulation. They follow

the laws of paper money circulation. In addition, when banknotes are issued by

loans collateralized by state bonds or unsecured loans to the government, they also

follow the laws of paper money circulation.

Thirdly, the

banknotes guaranteed by bullion of gold and silver follow the laws of metal

circulation. … Nevertheless, the banknotes by purchasing bullion are still just

commercial money (Okahashi [1957] p.215).

According to

Okahashi, banknotes issued by lending on the securities or the bullion follow

the laws of metal circulation because the money the borrower paid to buy them

is just taken over by bank lending. In

short, no money increases. (ibid., p.195)

It may be

difficult to understand that “the banknotes by the purchase of bullion are still

just commercial money.” Since commercial money is a direct payment promise by

the issuer (ibid.,p.195), the banknote issued in exchange for gold is the

commercial money for the bank. The bank’s liability becomes the credit money, when

the bank gives credit by handing over its liabilities at sight in exchange for

the commercial money of the debtor by bill discount (ibid., pp. 115-116).

A.3 Currency prescribed as the legal tender and compulsory currency

Okahashi

emphasizes that legal tender provision is not a panacea for the circulation of

money. The legal tender provision only legally confirms that banknotes based on

the circulation of bills are actually accepted as means of payment. Not all

legal tenders can circulate. Okahashi explains as follows:

The basis of the

circulation of monetary substitutes lies in each aspect of circulation. Just as

state paper money originates from the circulation of metal, the proper banknotes

originate from the circulation of bills and stand on the means of payment of

money. On the other hand, since the state paper money arises as a function of

the means of circulation of money, it directly enters the general circulation

as an intermediary for commodity circulation. However, since the proper

banknotes arise in place of commercial bills, they appear in commercial

circulation in the same way as commercial money. They are liabilities at sight,

very trusted, have a more comprehensive circulation than personal bills, and

seem as if they were cash (general means of circulation). However, banknotes

are still just bills, and the circulation of banknotes never stands on the

circulation of money. The provision of the banknote as legal means of payment

stands on its nature of bill circulation. Banknotes are accepted legally

because banknotes actually circulate based on the bill circulation. They are

fundamentally different from the state paper money as proper paper with “compulsory

power.” The state paper money does not circulate

depending on the fiat of the state. Instead, the metal circulation enables the state

paper money to circulate as a symbol of value in a limited amount. Similarly,

banknotes also do not circulate by the provision of legal tender. Instead, the

provision is just a “legal confirmation” that banknote is already widely

circulated instead of the money. The legal means of payment and the mandatory

circulating power are essentially different. Even if the banknote becomes legal

tender, it neither has “the mandatory circulating power” nor loses its essence

as a bill. Its nature does not change after the suspension of conversion.

Unlike state paper money, the inconvertible banknotes still circulate on the ground

of the nature of bills. (ibid., pp. 124-125)

Banks acquire financial

assets and issue banknotes (credit money) as their liability. The asset

supports the value of the banknote as guaranteed property. If the property is the

bill that is certain to be repaid in the future, the banknote is the proper

banknote. However, the banknote backed by other properties is non-proper.

A.4 Neutrality

of credit money and denial to credit creation

Famously,

Schumpeter maintained that credit creation creates new money as purchasing

power from nothing. The producer with new purchasing power gives birth to a new

product or a new production method. Interestingly, Okahashi’s denies such an

effect of credit creation on the real economy and claims the neutrality of

credit money. He explains the reason as follows:

Credit money as additional money appears through

various processes. … In whatever way it appears, the created credit money is a

new form of additional fictitious capital for the issuing bank, as for the portion not

guaranteed by gold or cash reserve on hand. However, even if it is privately additional

capital, it is socially neither “additional” capital nor additional net demand

as extra money. This additional credit money is the claim to the existing

social products made by economic development. Even though the sums of created

credit money “appear newly created side by side with the existing sums”

(Schumpeter [1951] p.99), there is already a contribution to social products

that should correspond to additional credit money. The money has been newly “created”

to realize the price of the additional social products. Unlike Schumpeter argues, it is never “certificates of future services or

goods yet to be produced.” (ibid.,p.101) Moreover, it is not the credit means of

payment, especially “created” without contributing to social products (pp. 173-174).

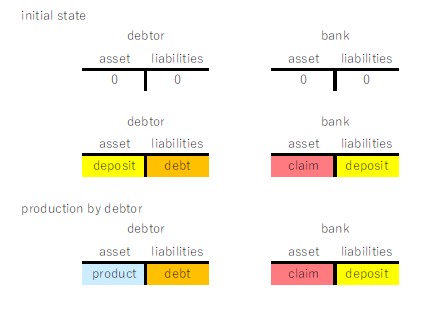

The following

figure shows a comparison between Schumpeter’s credit creation and Okahashi’s

denial of credit creation.

Fig. A-1

Schumpeter’s credit creation

Okahashi’s denial of credit

creation

In Schumpeter,

the money created by banks allows borrowers to hire workers and buy means of

production to make new products. Credit creation has a significant impact on

the economic process.

In contrast, in

Okahashi, the commodity the borrower buys already exists, and newly created

credit money realizes the value of the seller’s commodity. The new credit money

only corresponds to the value of the existing commodity. Thus, credit money is

neutral to the economic process.

コメント

コメントを投稿