注目

- リンクを取得

- ×

- メール

- 他のアプリ

Theories of credit money in Japanese Marxian economics: 2 Credit creation and endogenous money supply theory in Uno theory

B. Credit money in Uno school and

controversy

B.1 Kozo Uno’s criticism of Marx’s credit theory

Logically, Marx

starts credit theory by dividing one capital into ownership of capital and

function of capital. Each becomes a money capitalist and a functioning

capitalist as their personalization. In other words, money capitalists exist apart

from functioning capitals. Credit is the lending and borrowing of capital

between the two parties. The relationship between the two determines the level

of interest rate. Note that the interest rate does not follow the same law as

the production price of commodities. Marx mainly treats the money supply as

exogenous, although he also refers to elastic money supply as fictitious

capital (ex. Marx[1981] p.589). Marx asserts that money is gold and the source

of loan capital is outside the functioning capital. If the money supply is

inelastic, it would be easier to explain the catastrophic crisis.

However, Uno

criticized Marx for separating money capitalist from functioning capitalist

(Uno [1977] p.120). The principle of political economy assumes that each

capital tries to maximize its profit. Therefore, it cannot suppose the money

capitalists who are satisfied with a lower rate of interest although they could

earn a higher rate of profits with their capital.

Instead, Uno argued that parts of the money capital

are temporarily idle for various reasons in the capital reproduction and are sources

of funds to lend(ibid., p.110). They lose the use-value for the owner but will be needed soon. Thus, such

money capital temporarily becomes a commodity as use-value for others. When the

funds (money capital) are lent, its rent is the interest rate. In short, interest

is the price for the use of funds for a definite period of time. (ibid., pp.121-122)

Uno, as well as Marx, assumed that the supply and demand of money (fund) determines

the interest rate level. However, unlike Marx, Uno emphasized that the loan

funds are from temporarily inactive funds in the capital reproduction process

and increase or decrease in the business cycle.

Uno further

utilizes his theory of interest rate to explain the crisis. When the profit rate

declines at the end of the boom due to wage increase, idle money capital will

decrease, and the interest rate will rise rapidly. Then, when the interest rate

increases above the profit rate, a crisis happens.

Thus, Uno

inherits Marx’s way of the exogenous money supply, although he refers to

issuing banknotes depending on the bank’s reserve money (ibid., p.111).

However, when

credit money can increase elastically by lending, money holders need not be

supposed as sources of funds. In addition, the interest rate cannot be

determined by the supply and demand of the money. Instead, it should be

determined by the competition among capitals and the general rate of profit in

the capitalist economy.

B.2 Development of the theory of credit creation: Yamaguchi

Yamaguchi, a theorist of Uno school,

explains that credit creation is creating current purchasing power in

anticipation of future return. He theoretically argued that credit creation takes

place at commercial credit before bank credit.

He indirectly criticizes the

concept of fictitious capital of Marx. The debt of a bank beyond the reserve money

of the bank is not fictitious, but the whole debt is backed by the claim of

banks.

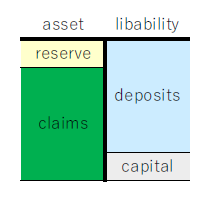

Let us illustrate to make the following explanation easier to understand.

Fig. B-1

Yamaguchi explains the credit

creation as follows:

Recently, even

among Marxian economics, credit creation is often used more than just as a

popular word. Its contents are still variously understood by theorists, and its

theoretical provisions have yet remained ambiguous. It generally means creating

unreserved liability that functions as the purchasing power. In other words,

traditionally, it means the banks increase lending by creating the debt

(banknotes or deposits) beyond their cash reserves (sometimes called primary

deposits). In addition, it has been thought to be unique to bank credit, and

its internal relationship with commercial credit has been largely unquestioned.

Such a conventional

view of the bank’s credit creation emphasizes that it creates money beyond its

reserve. … However, even if the created banknotes and deposits exceed its

reserves, they are made by loans such as bill discounts and backed by the loan

receivables, not cash reserves. In other words, bank liabilities are the

purchasing power based on the fact that loan receivables are repaid after a

certain period of time. Therefore, the essence of what is referred to by the

term “credit creation” is not the money creation beyond the reserve, which is

superficial and less meaningful. Instead, it should be a substantive function

of creating current funds by anticipating future acquisition of funds.

Thus, credit

creation has already emerged in commercial credit before bank credit, and the

internal relationship between credit creation by banks and commercial credit

becomes clear. In other words, the bank credit only lifts the restrictions on

the credit creation in the commercial credit and substitutes for the commercial

credit. Commercial credit is the basis of credit creation by banks. The credit

creation through commercial credit is more direct than bank credit in

anticipating future fund reflux. The bank credit also stands on the

anticipation of the future money return, but the anticipation is indirect.

Therefore, the bank reserve seems to support the bank credit. For that reason,

the conventional view may have emphasized the creation of money beyond reserve

money (Yamaguchi [1984] pp. 44-46).

Note that the difference between commercial

credit and bank credit. The debtors’ money acquisition backs both commercial

credit and bank credit. Nevertheless, bank credit seems to be backed by the bank’s

reserve.

Let us consider the

substitution of a bank for commercial credit. At first, suppose that capital A

is short of money reserve due to temporary stagnant sales of its commodities.

To continue production, capital A can buy raw materials from capital B in

postpaid credit. The assets of capital A increase by the price of raw

materials, and its debt increases by the same price simultaneously. On the

other hand, capital B (seller, creditor) receives claims (commercial bills) on

A instead of cash.

Fig. B-2

after credit trading

Fig. B-3

The creditor

anticipates that the debtor’s commodity will be sold and monetized in the

future and allows the postpaid dales. The creditor does not lend money directly

to the debtor.

Subsequently,

suppose the banking capital buys the claim from the creditor and pays with

self-addressed liabilities at sight, such as deposits or banknotes.

Fig. B-4

The deposit currency

in the creditor’s asset is backed by the claim in the bank’s asset. Finally, it

is backed by the future money from the future sale of the commodity in the

debtor’s asset. Subsequently, the creditor can buy commodities with the

deposits. Thus, credit money emerges from commercial credit and circulates

without the proper money.

Consequently, Yamaguchi

argues that the circulation of convertible banknotes mainly stands on the smooth

repayment of the claims held by the issuer’s bank.

Yamaguchi

explains the conversion and the credit money:

Firstly, let us consider promissory notes and

convertible banknotes. Although the bill is materially a piece of paper, it is

received by the commodity seller and acts as a de facto means of purchasing.

The rationale is that the receiver trusts the debtor will pay in the future. The

basis of the trust is the debtor’s smooth reproduction process. The convertible

banknotes are received, for the moment, because they are liabilities at sight

(money claim), and their payment is trusted.

Nevertheless, the basis of trust is that the bank

or the banking organization would smoothly receive repayment from their financial

assets. More generally, the convertible banknotes can circulate as de facto

money, based on the smooth process of social reproduction (Yamaguchi [2000] pp.194-195).

B.3 Self-contained

Credit theory of money: Yoshida

Satoru Yoshida had worked for the Japanese

Bankers Association for a long time and then became a university professor. He was

a practitioner economist rather than a theorist but exchanged with economics

scholars, including the Uno school.

Uniquely, he asserts that all the existing

money is credit money endogenously issued by bank lending. In addition, he denies

other exogenous money such as gold and fiat money. Usually, the theorists of

endogenous money supply assume fiat money supplied exogenously by central banks

or governments, apart from credit money by commercial banks. However, not just

commercial banks, Yoshida argued that the money issued by the central bank is

also credit money, not fiat money. Yoshida summarizes as follows::

In modern times,

all money (central banknotes, deposit currency) is credit money. (Auxiliary

money is not a problem here, although legally referred to as “money”). “Credit”

of credit money is “credit,” not “trust.” Credit money is money that occurs and

disappears in a credit relationship. However, this definition of credit money

is subject to many objections.

Banks provide

financial intermediation while creating money as deposits through credit

creation. Then, banks must replenish their reserves. The reserve is supplied by

the central bank as a bank of banks. (Reserve is needed after, rather than

pre-existing reserve enables credit creation. The Phillips-style theory of

multiplier credit creation is reverse causality. )

For deposits to

function as money, systems such as bill clearing and exchange trade are formed.

(These are deposit transfer systems.)

The essence of a

central bank is a “bank of banks.” Banknotes and central bank deposits are only

issued through financial transactions. Even inconvertible banknotes are not

fiat money.

People get

banknotes through the withdrawal of deposits. Deposits are promises to pay

banknotes, but deposits must exist first to increase banknotes.

The Central bank

accommodates to demand for banknotes and central bank deposits. However, how it

accommodates (financial adjustment) can determine short-term market interest

rates and affect general rates of interest. This is the basis of monetary

policy (Yoshida [2008] p.15).

Interestingly, Yoshida

uniquely uses the term “credit.” Usually, “credit” of credit money means “to

trust the promise of the bank issuing credit money to pay the proper money.”

That is, the holder of credit money trusts the bank. However, Yoshida uses the

term “credit” to mean “to trust the debtor receiving the credit money to pay

off the debt.” That is, the bank trusts the debtor. By interpreting in this

way, Yoshida can discuss credit money without any proper money.

The commercial

banks are obliged to hold the central bank money preparing for payment of

deposits. Then, can the central bank money circulate by becoming fiat money by

the legal tender provision? Yoshida goes back to the convertible banknotes and

explains the basis of circulation of central bank money regardless of

conversion.

Were the

convertible banknotes able to circulate due to convertibility? If so, inconvertible

banknotes could circulate only by the provision of legal tender. However, even

if a currency is forced to circulate as legal tender, it could not spread, or

even dollarization could occur when suffering from severe inflation. When even

inconvertible banknotes are managed well, they can circulate without any

problems. Certainly, convertibility was necessary to enhance the credibility of

banknotes, but was not the actual basis for circulation the ways to issue

banknotes? In short, at first, there are credit relationships in economic

transactions. Then, as the substitute of the relation, the credit money is

issued, whether a banknote or a deposit currency. In other words, does the

valid rationale of circulation exist in the issuance and return of money grounded

on reproduction? (Yoshida [2002] p.78)

“The ways to

issue” means that fiat money is issued by government spending while credit money

is issued by lending. Fiat money has no backing assets, whereas banknote as

credit money holds a backing asset such as financial claims and bonds. As long

as the backing asset is sound, the banknote can circulate.

Even inconvertible

banknotes do not lose their debt nature. Here, Yoshida appreciates the well-known

explanation of the debt nature of inconvertible banknotes in Nishikawa[1984].

Nishikawa says that the bank’s debt is paid off by banknote holders buying

commodities in the market rather than directly requesting the central bank to

pay off (Nishikawa [1984] p.47). Nishikawa assumes the debt nature of the

inconvertible banknote is not a direct relationship between debtor and creditor

but the central bank’s debt to the entire commodity society. Based on this

explanation by Nishikawa, Yoshida explains as follows:

Price stability

(maintenance of currency value) is essential for the issuer of inconvertible

banknotes to guarantee their ability to pay off. It is an obligation of private

law for the issuer of inconvertible banknotes to maintain the trust of banknote

holders rather than a public obligation. Financial textbooks say the goals of

monetary policy are stabilizing prices, balancing international payments, and

maintaining full employment. Nevertheless, it is said that the final

destination should be stabilizing prices because of maintaining the debt nature

of banknotes, including other debts of the central bank (Yoshida [2002] p.128).

Just as the commodity

producer should guarantee the quality of his commodity, the bank should maintain

the magnitude of the value of the credit money it issues. The magnitude of the

value of the money is the reciprocal of prices.

However, Yoshida’s

theory has the problem of discussing credit money without explaining the money.

In short, it is “a theory of credit money without any theory of money.

B.4

Yoshida-Yamaguchi Controversy

Yamaguchi

criticized Yoshida’s theory of credit money as follows:

“The endogenous

money supply theory,” which Yoshida seems to support, denies that the pre-existing

money is lent and maintains that, conversely, money arises by the lending. Indeed,

money arises from the loan relationship, and similarly, the modern inconvertible

central banknote also comes into existence through the credit mechanism.

However, since lending is a lending of money, we should first assume the

concept of money before the lending. If we consider that money arises from money

lending, we will fall into eternal circular reasoning. After the circular reasoning

is cut off, the theory of endogenous money supply can hold. In other words,

theoretically, “the cash money is the premise.” Nevertheless, this does not

mean agreement with the Phillips-style theory of credit creation. (Yamaguchi[2008]pp.84-85)

In response,

Yoshida wrote:

It shows the

theorist’s way of thinking, but actually, such cash money never exists. Nevertheless,

“theory” resting on such cash money seems to diffuse. It would ground credit

theory on inconvertible banknotes (fiat money) with mandatory circulating power.

Not to say, Yamaguchi would agree with the “theory.” Hopefully, an approach

“breaking the circular reasoning” will emerge. (Yoshida [2008] p.24 )

B.5 How

to break the circular reasoning of credit money

As criticized by

Yamaguchi, Yoshida’s theory of credit money is circular reasoning that “a

promise to pay money is money.” If credit money is a promise to pay something, what

is this “something”? If we present something, we can cut off the circular

reasoning.

(1) The first way

is to “cut off with legal tender.” The government stipulates what can pay off

the debt between private agents, and the government provides it as legal tender.

Because all the agents owe the monetary debt by buying commodities in the

commodity society, the legal tender can circulate even with no value. The

government does not necessarily issue it. The promise to pay it is credit

money.

(2) The second

is to “cut off by tax collection.” The government stipulates what can pay off tax.

Because all the agents owe tax obligations to the government, The means to pay tax

can circulate even with no value or with no mandatory circulating power. The

government does not necessarily issue it. The promise to pay it is credit

money. This way is often used by Chartalists.

(3) The third is

to“cut off with gold money.”

As the theory of value-form shows, gold is selected as a money commodity among all

commodities that have value in themselves. Because gold has its value and all

agents can exchange all commodities with it, it can circulate. The promise to

pay it is credit money. However, as Yoshida says, gold is no longer money.

(4) The fourth is

to “cut off with commodity money.” The way emphasizes that the issuer

of credit money has financial assets backed by commodity value. We explain it in the next section.

コメント

コメントを投稿