注目

- リンクを取得

- ×

- メール

- 他のアプリ

Theories of credit money in Japanese Marxian economics: 3 Commodity theory of money in modern Uno theories

C. Commodity

theory of money in modern Uno theories

C.1

Credit money as commodity money

Obata, a current

representative theorist of modern Uno school, explains “commodity money in a

broad sense” in his textbook of the principle of political economy:

The commodities have

specific use-value, such as linen and coat. There is no general use-value.

Since the commodity has some “specific” use-value, its “general”

exchangeability for others is constrained. Conversely, as long as a commodity

is “valued,” any commodity has the qualification to become money potentially,

that is, the nature of money. Therefore, money is a special commodity based on

the nature of money inherent in commodities. The position to think this way is the

commodity theory of money. The theory of the value-form of the commodity

inevitably reaches the commodity theory of money (Obata [2009] p.44).

Commodity money consists

of material money and credit money. The material money is defined as follows:

Material money is

the money which the physical body of the specific commodity becomes as it is

(ibid., p.45)

Obata explains

the credit money as follows:

The commodity

theory of money is often said to consider only material money or metal money as

money. However, it is a misunderstanding that arises from equating commodities

with things. Originally, commodities

are in a particular state of things with use-value for

others and always have value on the backside. The commodity theory of money

explains money on the basis of the value of commodities. The theory does not

argue that money is made of physical material without the value of commodities.

Commodity money includes material money but is not reduced to it. Then, the

commodity value can be externalized and self-supporting in the form of a monetary

claim. The credit is money becoming self-sustaining in the form of a claim

(ibid., pp. 46-47)

Theoretically, all the commodities express

their value by one thing, and their exchangeability concentrates on the same

thing. The thing becomes commodity money. Nevertheless, money can take two

forms: material money and credit money. Marx and Uno have explained the

material money sufficiently. Obata discusses the polymorphism, that money takes multiple forms, in Obata [2013]. Although he shows the basic concept

of credit money, he does not sufficiently succeed in a detailed argument.

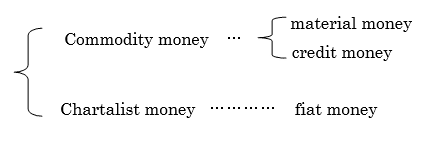

He classifies multiple forms of money as

follows:

ibid., [2009] p.

48

Importantly,

commodity money consists of material money and credit money. Currently, the

fiat money does not circulate except auxiliary money in

a limited amount. Chartalist

money stands on the chartalist theory of money. Obata explains the :

The idea opposed to the commodity theory of money is the chartalist

theory of money. The chartalist theory assumes that even non-commodities can be

thrown as money from outside the market. If the material of the chartalist

money is paper, it is the state paper money. However, regardless of material,

it is widely called fiat money. The theory that the agreement of people can

create money independently is a kind of the chartalist theory. Because credit money and state paper money are

usually made of the same material, paper, they are grouped as paper money, opposed

to metal money. However, it is a mess due to the appearance of money. The

commodity theory of money can explain both material money, including metal

money, and credit money. On the other hand, fiat money, including state paper

money, stands on the chartalist theory of money and is conceptually

different from credit money (ibid., pp. 47-48).

From the above quotation, the meaning of Fig.

C-1 is clear.

Here, let us develop the theory of credit money

backed by the issuer’s assets. It continues from (4) the way to “cut off with commodity money” at the

end in section B. The structure of credit money be illustrated in the balance

sheet as follows:

Fig. C-2

Because credit

money is issued by bank lending, the bank holds a claim on the borrower. The

borrower has assets that guarantee repayment. The assets may be commodities for

sale, production means generating revenue, or the ability to receive wages or

tax revenues. It is easy to show the basis of the value of credit money in this

static manner.

However, it is

challenging to elucidate the logical genesis of credit money, as with the

value-form theory. Currently, theorists of the Modern Uno school propose several

methods to elucidate credit money’s genesis based on the value of a set of multiple

commodities without gold or fiat money.

C.2 Determination

of the level of interest rate

Credit money is issued by banks, which are a

kind of capital pursuing valorization. Therefore, the interest rate should be where

banking capitals can gain the general rate of profit. Here, Obata shows the relation between the interest rate and profit

rate as follows:

Bank net profit

rate = {(Q

× i - Q' × i' ) – k – d } / P

= the general rate of net profit of industrial capitals

Where: Q

is loan quantity, i is lending interest rate, Q’ is deposit quantity, i’

is deposit interest rate, k is circulation cost (various expenses in bank

business ), d is bad debt loss, and P is bank’s equity capital (ibid., p. 238)

The interest

rate is determined, so that bank’s profit rate in this formula is at the same

level as the general rate of profit of industrial capitals. In this way, the

mechanism of money creation can be explained in a self-contained manner in the

capital pursuing profit. However, to fully understand this relationship, it is

necessary to know the circulation cost, net profit rate and gross profit rate,

and downward dispersion of net profit rate, which modern Uno theories propose.

- リンクを取得

- ×

- メール

- 他のアプリ

コメント

コメントを投稿